Azembeh, T*; Iorlamen, R.T., Abu .O.

Department of Agricultural Economics, Federal University of Agriculture, Makurdi, P.M.B. 2373, Benue State, Nigeria

| ARTICLE INFORMATION | ABSTRACT |

| Corresponding author: E-mail: azembehterna@gmail.com Tel.: +234-8086213504 Keywords: Intensity Livelihood Diversification Food Security Arable Small-scale Received: 30.10.2023 Received in revised form: 11.11.2023 Accepted: 15.11.2023 | The study analyzed the intensity of livelihood diversification and food security among arable crop small-scale farming households in Benue State, Nigeria. The study adopted a survey research design that made use of primary data. The data collected were analyzed using frequency, percentages, means, and food security index. The results on socio-economic characteristics showed that most arable farmers are in their productive age (40 years), about 61.7% of males are majorly involved in farming and 89.4% are married. Arable farmers in the area spent at least 10 years in school had a household size of at least 7 members, and an average farm size of 5.55 hectares with an average annual income of N 461, 785.53. The result of livelihood strategies engaged in and income realized showed that most (23.3 %) of respondents were more diversified in cultivation of cassava with average income earned of N 82,688.89, 22.2 % diversified into yam cultivation with average income earned of N166,257.14, 18.3% diversified into rice cultivation and earned N139,757.58, 8.3 % into soybeans with average income earned of N129,130.; 6.7 % into guinea corn and earned N143,750.00, 6.1 % into maize and earned N 89,444.44, 5.0 % into cowpea (beans) and earned N101,428.57, 3.9 % into groundnuts and earned N 67,533.33, 1.1 % into sesame (beniseed) and earned N 107,500.00, and 0.6% into bambaranut and earned N 70,000.00. The results of the Simpson index showed a mean diversification index of 0.7059 which falls between the index of 0.61 and 0.90 indicating that, small-scale farming households are highly diversified in various diversification activities. The results on the constraints to diversifying livelihoods of respondents in the study area showed that inadequate access to credit (99.4 %), insufficient market price of commodity (80.0 %), and unstable electricity (78.3 %) were the most constraints. The study concludes that livelihood diversification strategies are healthy for income realization during the off-season when farmers who depend on rain are no more in the cropping season. Agricultural policies should be targeted toward livelihood diversification strategies that ensure the food security status of small-scale farmers. |

1. INTRODUCTION

In Nigeria, agriculture is the source of food for the populace as well as raw materials for the agro-industries and contributes about 33 % to the Gross Domestic Product of the nation (Bureau of African Affairs, 2010). The sector employs about one-third of the total labor force and provides a livelihood for the bulk of the rural populace (Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, FMARD, 2006). Nigeria is an agrarian society with about 70 % of its population (approximately 140 million) small-scale farmers majorly participate in agricultural production to provide food for the teeming population and raw materials for industrial production (NBS, 2020).

The Nigerian agricultural landscape is basically dominated by small-scale farmers who form about 90 % of the farming population most of which are arable crop farmers. In most developing countries, the importance of nonagricultural activities is increasing and it is estimated to account for 30-50 % of rural incomes (Omofonwan, 2018). Several international organizations like the Overseas Development Institute (ODI), the Department for Foreign and International Organizational Development (DFID), and many others promote and argue that livelihood diversification acts as a safety net for poor rural households.

The development economics literature has identified two main factors that drive diversification among arable crop farming households in developing countries like Nigeria. These factors are broadly classified into pull factors and push factors. Farm households can be pulled into the off-farm sector so as to earn high returns to labour or capita and the less risky nature of investment in the off-farm (Kilic et al. 2019).

The push factors that may drive off-farm income diversification include; the need to increase family income when farm income alone cannot provide sufficient livelihood, the desire to manage agricultural production and markets risks in the face of a mission insurance market, the need to earn income to finance farm investment in the absence of a functioning credit market (Babatunde and Quim, 2013).

Many studies (Yared, 2012; Degefa, 2015) have shown the need and importance of diversification for households’ survival and secured livelihood. A household, which depends on few livelihood strategies, is very vulnerable. Diversification means there could be other sources of livelihood for the household to fall back on. Rural people in Africa and Nigeria, in particular, have diversified their economic activities to encompass a range of productive areas that include farm and non-farm income-generating activities (Idowu, 2014).

The main driving forces of diversification are: to increase income when the resources needed for the main activities are too limited to provide a sufficient means of livelihood (Nghiem, 2010), to reduce income risks in the face of the mission insurance market (Dilruba and Roy, 2012), to exploit strategic complementarities and positive interactions between different activities and to earn cash income and finance investment in the face of credit failures (Nghiem, 2010).

The problem of food security in Nigeria has not been adequately and critically analyzed despite various approaches to addressing the challenges.

The government has introduced several projects and programmes including livelihood activities to improve the agriculture status of small-scale farmers and boost food production in the country.

However, the empirical records of many of these programs and projects are not impressive enough to bring about the expected transformation of small-scale farming households (Ihimodu, 2014). Today, the problem continues to exist at an increasing pace as more than 900 million people around the world are still food insecure (FAO, 2010). According to Adebiyi (2012), Nigeria remains a net importing nation, spending about N1.3 billion on importing basic food items annually.

The food security problem in Nigeria is pathetic as more than 70 percent of the populace live in households too poor to have regular access to the food that they need for healthy and productive living with an increasing high level of poverty (Babatunde et al. 2017).

There exist studies on diversification strategies and food security in Nigeria. Baharu (2016) studies the effect of livelihood diversification on household income; Abu and Soom (2016) focused on factors affecting food security in rural and urban farming households in Benue State; Ahungwa (2013) studied economic analysis of household food insecurity and coping strategies in Osun state, Nigeria. However, there are perhaps no known studies on livelihood diversification and food security among small-scale arable farming households in Benue State, Nigeria.

Motivated by the above gaps, empirical evidence that will be generated by this study will help to fill the knowledge gap in the literature. Using Benue State, Nigeria as a typical ecological region, this study will focus on the analysis of livelihood diversification and food security among small-scale arable farming households in Benue State, Nigeria.

2.0 METHODOLOGY

2.1 Study Area

The study was conducted in Benue State, Nigeria. The State capital is Makurdi. Benue State lies within the lower river Benue trough in the middle belt region of Nigeria. Its geographic coordinates are longitude 7° 47′ and 10° 0′ East. Latitude 6° 25′ and 8° 8′ North; and shares boundaries with five other states namely: Nasarawa State to the north, Taraba State to the east, Cross-River State to the south, Enugu State to the south-west and Kogi State to the west.

The state also shares a common boundary with the Nord-Ouest Province, claimed by both Ambazonia and the Republic of Cameroon on the south-east. Benue occupies a landmass of 34,059 square kilometers. Benué State consists of twenty-three (23) Local Government Areas.

The state is populated by several ethnic groups such as; Tiv, Idoma, Igede, Etulo, Abakpa, Juku, Hausa, Igbo, Akweya, and Nyifon. Most of the people are farmers while the inhabitants of the river areas engage in fishing as their primary or important secondary occupation.

The people of the state are famous for their cheerful and hospitable disposition as well as their rich cultural heritage. The State is a major producer of food and cash crops like yam, cassava, rice, groundnuts, and maize.

Others include sweet potatoes, millet, sorghum, sesame, and a wide range of others like soybeans, sugarcane, oil palm, mango, citrus, and banana. Irrigation farming along the banks of Rivers Benue and Katsina-Ala is a common feature.

2.2 Sample and Sampling Techniques

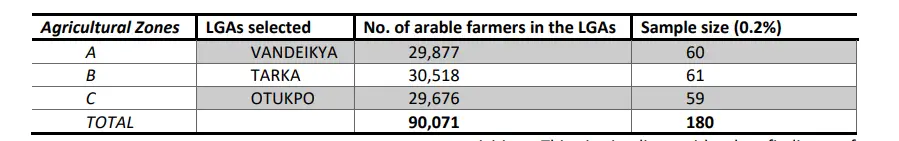

The population of this study consisted of arable crop small-scale farmers in Benue State. Multi-stage random sampling technique was used to select respondents for the study. In the first stage random sampling technique was used whereby, one (1) Local Government was randomly selected from each of the three (3) agricultural zones in Benue State (Zone, A, B, and C) which include Vandeikya, Tarka, and Otukpo Local Government Area respectively.

A total of 90,071 small-scale arable crop farmers were involved in the production of arable crops in the selected Local Governments according to BNARDA, (2020). In the second stage, a proportionate sampling technique was used whereby, a total of 180 respondents was selected using a proportionate distribution of 0.2%. The distribution of the sample in the three (3) selected Local Governments is presented in Table 1.

2.3 Methods of Data Collection and Analytic Technique

Primary data was used for this study. The data was collected through direct personal interviews with structured questionnaires. Trained enumerators who understand and speak the native languages perfectly were employed in the collection of primary data, while illiterate households were asked questions in the questionnaire, and answers were filled by the enumerators.

Data for the study was analyzed using descriptive statistics such as frequency, percentages, mean and standard deviation, and inferential statistics such as food security index (FSI).

Table 1: Sample Size Selection Plan Agricultural Zones

activities. This is in line with the findings of

2.4 Model Specification

2.4.1 Food Security Index (FSI)

Food Security Index was used to ascertain the food security status of respondents in the study. Food security index is given as below

3.0 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1 Socioeconomic Characteristics of Respondents

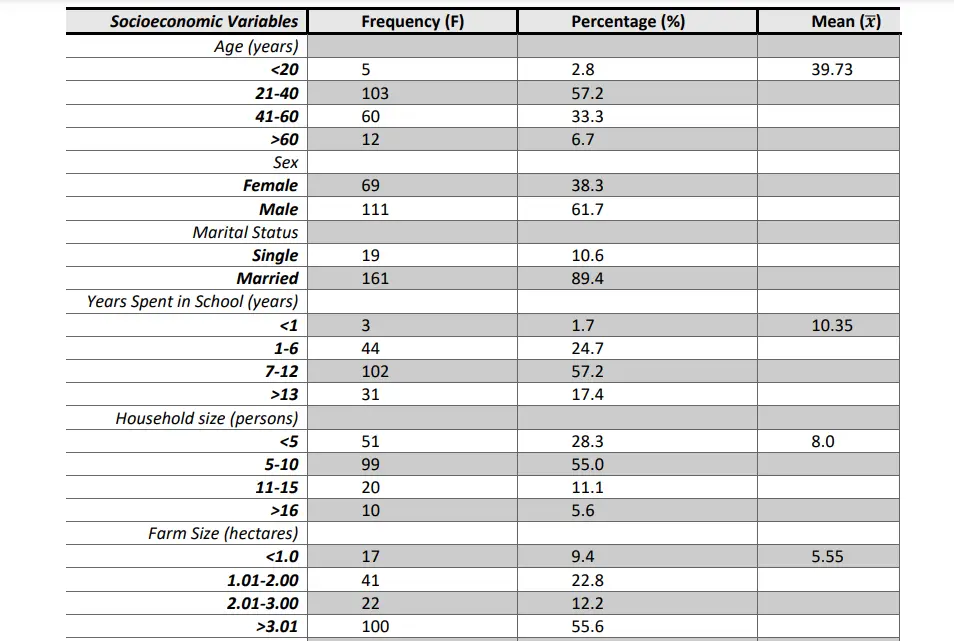

The socioeconomic variables of the respondents examined include: age, sex, marital status, years spent in school, household size, farm size, farming experience, extension contact and annual income.

Age (years)

The result in Table 2 showed that most (57.2%) of the respondents were between the age bracket of 21-40 years, 33.3 % were between 41-60 years, 6.7 % were more than 60 years and 2.8 % were less than 20 years of age. The mean age of respondents was 39.73 years.

This implies that most members of small-scale arable farming households are economically active and energetic in engaging in agricultural production which is an important factor that positively influences their involvement in varied diversification Tashikalma et al. (2015) and Afodu et al. (2020) that small-scale farmers in Benue State, Nigeria are still in their youthful age of 31 to 40 years. The findings was also agreed by Bayero et al. (2019) who pointed out that most small-scale farmers in Nigeria are between 30 to 40 years of age.

Sex

Table 2 also shows the distribution of respondents according to sex which indicates that the majority (61.7 %) were males while 38.3 % were females. This implies that most of the small-scale arable farmers in the study area are males. This is in line with the findings of Kuwornu et al. (2013) who reported that most farmers in Benue State, Nigeria are males. This also coincides with the findings of Gani et al. (2019) and Okpokiri et al. (2017) who reported that a larger population of arable crop farmers in Benue State, Nigeria were males.

Marital status

The findings on marital status revealed that a larger proportion (89.4 %) of respondents were married while just 10.6 % of the respondents were single. This shows that a larger proportion of the small-scale arable crop farming households in the study area were married. The implication is that most farmers who are married tend to try other sources of income and thus diversify into other options so as to obtain income to provide household needs.

This is in agreement with the findings of Matthew-Njoku and Nwaogwugwu (2014) who found out that most farmers were married. Also, Mohammed and Fentahun (2020) and Babatunde and Quim (2009) agreed that most arable crop farmers were married.

Years Spent in school

The analysis in Table 2 on the years spent in school by respondents revealed that most (57.2%) respondents spent between 7 and 12 years in school, 24.7 % spent between 1and 6years in school, 17.4 % spent more than 13years in school and 1.7 % spent less than 1year in school. The average years spent in school was 10.35 years. This implies that the respondents were literate and attained at least secondary education. This is in line with the findings of Gani et al. (2019) who posited that farmers in Nigeria were literate. Also in agree with the findings of Haddabi et al. (2019) that farmers attained at least a secondary level of education.

Household Size

The result on household size of respondents showed that most, (55.0 %) of respondents have a household size of between 5 and 10 members, 28.3 % have less than 5 members, 11.1 % have between 11and15members and 5.6 % have more than 16 members in their households. The mean household size of respondents was 8 members.

This implies that the respondents have a large household size to support family labor and thus engage in diversification. This finding disagrees with Amurtiya et al. (2016) who reported that the average household size of farmers was between 10 and 15 persons.

Also not in line with Sowamin (2018) who was of the view that the average household size of arable farmers was between 5 and 6 persons per household. In line with the findings of Audu (2017) who reported that cassava farmers in Benue State, Nigeria have a household size of between 5 and 10 persons.

Farm Size

The findings in Table 2 on farm size showed that most (55.6 %) own more than 3.01hectares of farm size, 22.8 % own between 1.01and 2.00 hectares, 12.2 % own between 2.01 and 3.00 hectares of farm size and 9.4 % own less than 1.0 hectares of farm size. The respondents own a mean farm size of 5.55 hectares for the production of arable crops.

This implies that respondents were medium-scale farmers who cultivate small portions of land which are often fragmented. Cumulatively, they have a reasonable farm size which will encourage their income earning and be involved in diversification since they will use the fragmented lands to grow different crops.

This disagrees with the findings of Sowami (2018) who reported that farming households in Ogun state hold between 2-3 hectares of farm size. Also disagrees with Haddabi et al. (2019) who reported an average of 2.95 hectares of farm size for rural farming households in Adamawa State, Nigeria.

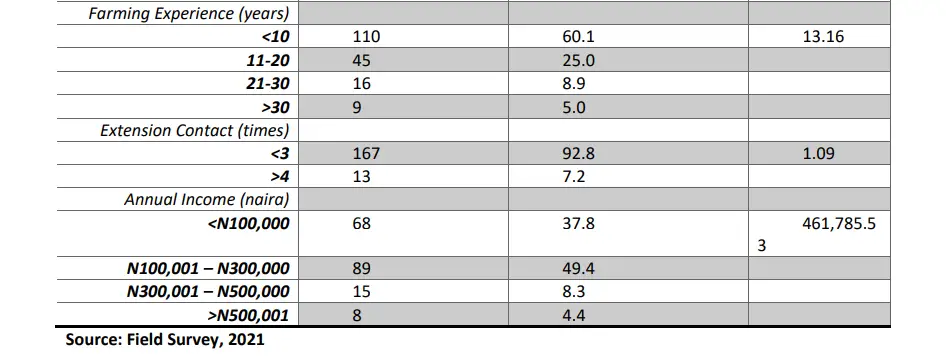

Farming Experience

Analysis of farming experience showed that a larger proportion (60.1 %) of respondents have less than 10 years of farming experience, 25.0 % have between 11 and 20 years of farming experience, 8.9 % have between 21 and 30 years and 5.0 % have more than 30 years farming experience. The mean farming experience of respondents was 13.16 years. This implies that respondents in the study area are experienced farmers since they have spent many years in farming.

This is in contrast with Abiodun et al. (2019) who reported that arable crop farmers have more than 10 years of farming experience. Also in contrast with the view of Sowami (2018), farmers had between 10-20 years of farming experience in cassava farming.

Extension Contact

The result in Table 2 showed that the majority (92.8 %) of respondents made less than 3 times contact with extension agents and 7.2 % made more than 4 times contact with extension agents. The average extension contact of farmers was 1.09 times. This implies that farmers do not often meet with extension agents. This may also be because of their diverse involvement with their farm enterprises since they will not be eager to wait and meet with extension agents. This is in line with the findings of Etuk et al. (2018) who reported less than one-time meetings with extension agents. Also agrees with Umeh et al. (2013) who reported a mean contact of 2 times with extension agents.

Annual Income

The results of annual income as presented in Table 2 showed that 49.4% of respondents earned between N100,001.00 and N300,000.00 annually, 37.8% earned less than N100,000.00 annually, 8.3% earned N300,001 and N500,000 annually and 4.4% earned N500,001 annually. The average annual income of respondents was N 461,785.53 annually. This implies that respondents are low-income earning farmers who are classified as operating on a small scale since they make less than N 500,000.00 annually from their farming.

This is in line with Amurtiya et al. (2016) who reported that small-scale farmers earn less than N500,000.00 per annum. Also in line with Sowami (2018) who reported that cassava farmers earn less than N500,000.00 annually as income from farming.

Table 2: Socioeconomic Characteristics of Respondents n = 180

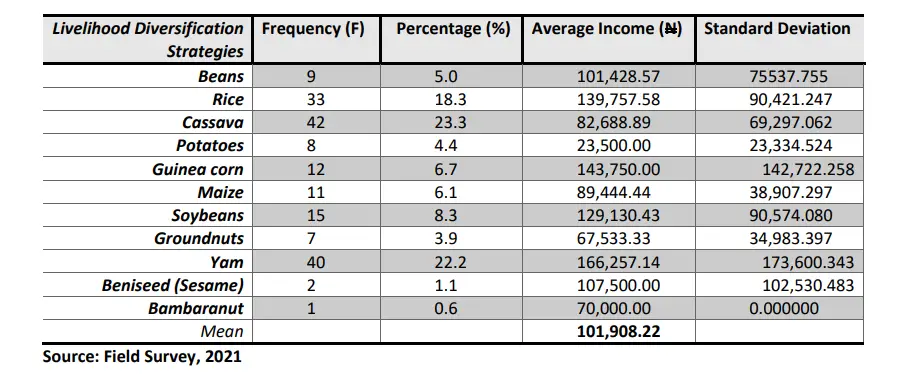

3.2 The Livelihood Strategies Engaged in and Income Realized from them

The result on livelihood strategies engaged in and income realized from them as presented in Table 3 showed that the majority (23.3 %) of respondents were more diversified in the cultivation of cassava with an average income earned to be N82,688.89, 22.2 % cultivated yam with an average income of N166,257.14, 18.3 % cultivated rice and earned income of N139,757.58, 8.3 % cultivated soybeans with average income earned of N129,130.; 6.7% cultivated guinea corn and earned income of N143,750.00, 6.1 % cultivated maize and earned N89,444.44, 5.0 % cultivated cowpea (beans) and earned N101,428.57, 3.9 % cultivated groundnuts and earned N67,533.33, 1.1 % cultivated sesame (beniseed) and earned N107,500.00, and 0.6% cultivated Bambara nut and earned N70,000.00.

This implies that most of the respondents were involved in diversification by participating in more than one farm activity thereby cultivating several crops. This is in line with Yusuf (2013) who reported that most farming households diversify their farming into cultivating other crops other than one type of crop.

Table 3: Livelihood strategies engaged in and income realized from them

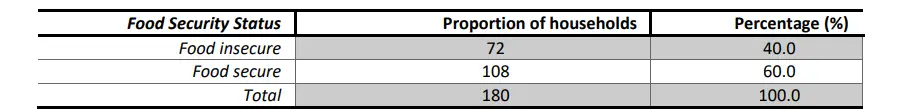

3.3 Food Security Status of Farming

Households

Table 5 presents the results on the food security status of farming households. A mean per capita annual food expenditure of N 97,494.44 was used to classify the households either as food secure or food insecure. The result showed that the majority (60.0 %) of respondents were found to be food secure while 40.0 % were found to be food insecure.

This implies that most households were food secure, but attaining food security is still a challenge in the study area since households (40%) experience chronic food insecurity problems annually. The result disagrees with the findings of Biam and Tavershima (2020) who found that 43.1% of the households were food secure, and 56.9 % were food insecure in their study on the food security status of rural farming households in Benue State, Nigeria.

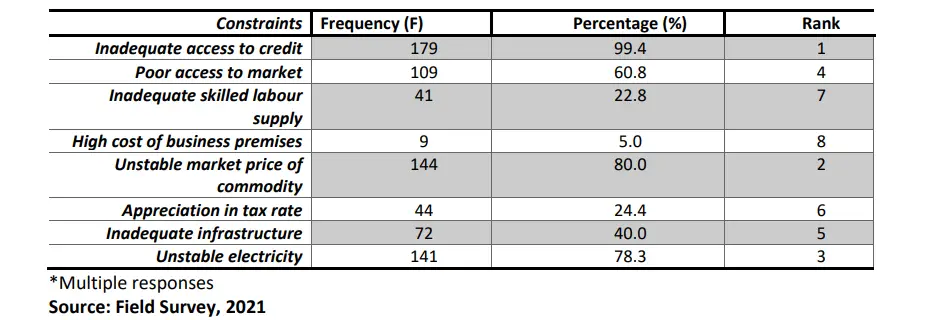

3.4 Constraints to diversifying livelihoods

Multiple responses were used to determine the constraints toward farmer’s diversification into other enterprises. It was found that; inadequate access to credit, the unstable market price of the commodity, unstable electricity, poor access to market, inadequate infrastructure, appreciation of tax rate, inadequate skill labour supply, and high cost of rent for business premises all stand as bottlenecks for farmers achieving diversification.

Inadequate access to credit

The result shows that inadequate access to credit (99.4 %) was the most identified constraint hindering farmers from diversifying to other enterprises. Most farmers are willing to get engaged in other enterprises so as not to be entangled to only one enterprise but they are handicapped due to the inadequate and unavailability of credit support from the government and other financial institutions.

This implies that, farmers who are poor and are not supported with credit facilities will tend to stick to the cultivation of a particular cash crop. This is in line with the findings of Saha and Bahal (2014) and Degefa (2015) who found that farmers’ inability to obtain credit facilities restricts their potential to harness opportunities from other crop enterprises.

Table 4: Food security status of farming households

Source: Field Survey, 2021

Unstable market price for commodities

The result shows that about 80.0% of respondents were of the view that instability of market price for commodities is one of the problems hindering farmers from achieving diversification. Unstable market prices make farmers lose track of appreciable prices of commodities. This discourages farmers from diversifying since they thought, they might lose their initial capital if invested in some crop enterprises. This is supported by Ellis and Freeman (2017) who found that continuous reductions in the prices of commodities discourage farmers intentions of investing in such enterprises. Also, Dereje (2016) reported that price instability of agricultural products especially when prices are on the decrease prevents farmers from cultivating crops whose prices are low but tend to cultivate crops whose prices tend to increase.

Unstable electricity

The result also reveals that 78.3 % of respondents identified unstable electricity as another constraint towards attaining diversification. Most of the farmers who indulge in the processing of products to add value so as to receive appreciable prices are hindered due to the incessant electricity power supply. Electricity power supply lowers the processing cost and when unstable, it makes farmers who carry out processing activities spend more money in processing agro products.

According to Omonfonwam (2018) unstable electricity prevents most farmers from diversifying to crops that need value addition for appreciable prices. The findings are also supported by Martins and Lorenzen (2016) who pointed out that poor electricity supply prevents most farmers willing to invest in other crop enterprises from doing so considering the hike in prices of alternative sources of power.

Poor access to market

farmers from achieving livelihood diversification strategies. Some market structures prevent most farmers entry and this makes it difficult for most farmers who do not want to only stop at cultivation but also to explore the market opportunities not to participate in some livelihood diversification strategies.

This is in accordance with the findings of Onunka and Olumba (2017) who pointed out that, most farmers refuse entry into another crop enterprise since they cannot participate in market activities which are most a times profitable than just the cultivation of the crop.

Inadequate infrastructure

About 40.0% of respondents gave their responses amounting to acceptance that inadequate infrastructure is also a constraint towards farmers getting involved in other livelihood diversification strategies. This problem of infrastructure prevented farmers from enjoying economies of scale which could be provided by infrastructure facilities such as electricity, water supply, processing plants, warehousing, etc. This makes many farmers not explore other areas of investments and thus restricts their diversification abilities.

This is in line with the findings of Sowami (2018) who suggested that a lack of infrastructure prevents farmers from being involved in the processing and packaging of products. Also in tandem with the findings of Tshikalma et al. (2015) who opined that poor infrastructure activities prevent farmers from indulging in other production activities which are profitable.

Appreciation in tax rate

The study found that, about 24.4% of respondents agreed to appreciation of tax as a constraint towards livelihood diversification by farmers. This is so because, rural farmers are mostly involved in the production of crops and where there are high tax charges, the farmers tend to avoid this thus preventing them from getting involved in other livelihood strategies.

For instance, if there are high taxes for transporting agro-produce, farmer will tend to sell their produce at the farm gate to avoid further expenses on transportation since they are poor farmers. These findings coincide with that of Ihimodu (2014) who found that high market taxes prevent farmers from diversifying into marketing of products in the agricultural markets. Haddabi et al. (2019) also contributed that, most farmers do not get involved in the processing of agricultural produce due to the high cost of processing.

Inadequate skilled labour supply

The results revealed that, about 22.8 % of respondents were of the view that inadequate skilled labour supply prevents them from diversifying into strategies. Most farmers are unskilled and thus only produce their products and get them sold at the farm gate. They are not learned and thus lack marketing skills, communication skills, processing skills and much more. This by implication makes these farmers to become limited in selling their produce only at the farm gate. This is in tandem with the findings of Kuwornu et al. (2013) who found out those farmers who are unskilled findings if difficult to diversify into other areas of crop enterprises since they lack knowledge of some crop enterprises. Similarly, Kyeremeh (2014) reported that most unskilled farmers tend not to adopt innovations and thus finds it challenging to indulge in other livelihood activities with ease.

High cost of rent for business premises

The result also shows that 5.0% of respondents agreed on high cost of rent for business premises as another constraint preventing most farmers from getting involved into livelihood diversification strategies.

This shows that the cost of rent for warehouses, storage rooms, and shops is high and most farmers could hardly afford to pay. By implication, the cost of rent prevents farmers from diversifying into some livelihood diversification strategies.

This is in line with the findings of Kassie (2016) who found that farmers who wish to diversify their productions process into marketing and distribution become handicapped due to the high cost of rent for land. These findings also coincide with that of Kyeremeh (2014) who reported that the high cost of rent for assembling produce in the urban areas prevents most farmers from diversifying into transportation and marketing of agricultural produces which limits them to sale their produce at the farm gate.

Table 5: Multiple Responses on the Constraints to diversifying livelihoods

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The study concludes that a larger proportion of arable crop farmers are involved in livelihood diversification activities to improve income generation to take care of their household needs. This suggests that there is a need for arable diversification activities so as to provide food for the household, increase their income earnings and in turn boost agricultural and nonagricultural activities for a developed economy. Based on the findings of this study, it is therefore recommended that:

i. The government should provide access to credit facilities so as to encourage farmers’ easy swing into

livelihood diversification activities with benefits from the economy of scale.

ii. The government should formulate policies and provide infrastructure facilities to help farmers improve their income

iii.Agricultural policies should be targeted towards livelihood diversification strategies that ensure food security status of small-scale farmers.

REFERENCES

Abiodun, T.C.; Adewale, I.O.; Ojo, S.O. Evaluation of Choices of Livelihood Strategy and Livelihood Diversity of Rural Households in Ondo Stata, Nigeria. Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities., 2019, 5(1):17-24.

Abu, G.A.; Soom, A. Analysis of Factors Affecting Food Security in rural and Urban Farming Households of Benue State, Nigeria. International Journal of Food and Agricultural Economics, 2016, 4(1):55-68.

Adebiyi, B. Jonathan’s Agricultural Business plan. Nigeria Tribune, Wednesday 13 June, 2012. Afodu, O.J.; Afolami, C.A.l.; Balogun, O.L. Effect of Livelihood Diversification and Technology Adoption on Food Security Status of Rice Farming Households in Ogun State, Nigeria. Agricultural Socio-Economics Journal, 2020, 20(3):233-244.

Ahungwa, A. Economic Analysis of Household food Insecurity and Coping Strategies in Osun state, Nigeria. Unpublished Ph.D thesis, Department of Agricultural Economics, University of Ibadan, Oyo State, Nigeria, 2013.

Amurtiya, M.; Lumbonyi, C.A.; Abdullahi, A.; Olayiwola, S.A.; Yaduma, Z.B.; Abdullahi, A. Livelihood Diversification and Income: A case study of communities resident along the Kiri Dam, Adamawa State, Nigeria. Journal of Agribusiness and Rural Development, 2016. 4(42), 483-492.

Audu, O. Assessment of Household Consumption Pattern of Broiler Meat in Makurdi Local Government Area of Benue State, Nigeria. Project Submitted to the Department of Agricultural Economics, Joseph Sarwuan Tarka University, Makurdi, Unpublished., 2017.

Awoke, M. U.; Okorji, C. The Determination and Analysis of Constraints in Resource Use Efficiency in Multiple Cropping Systems by Smallholder Farmers in Ebonyi State, Nigeria. Africa Development., 2004, 39(3), 58-69.

Babatude, R.O.; Qaim, M. “Socio-Economics Characteristics and Food Security Status of Farming Households in Kwara State, North Central Nigeria”. Pakistan Journal of Nutrition, 2009, 6(1), 49-58.

Babatunde, R.O.; Qaim, M. Impact of Off-farm Income on Food Security and Nutrition in Nigeria. Food Policy, 2013, 35, 303-311.

Babatunde, R.O.; Omotesho, O.A.; Sholotan, O.S. Factors Influencing Food Security Status of Rural Farming Households in North Central Nigeria. Agricultural Journal, 2017, 2(3), 351- 357.

Baharu, G. Effect of Livelihood Diversification on Household Income: Evidence from Rural Ethiopia. Journal of Environmental studies Ethiopia, 2016, 4(5), 34-56.

Bayero, S.G.; Olayemi, J.K.; Inoni, O.E. Livelihoods Diversification Strategies and Food Insecurity Status of Rural Farming Households in North Eastern Nigeria. Economics of Agriculture, 2019, 1:68(1), 281-95.

Biam, C.K.; Tavershima, T. Food Ssecurity Sstatus of Rrural Hhouseholds in Benue State, Nigeria. African Journal of Food Agriculture, Nutrition and Development, 2020, 20(2),1-18.

BNARDA. Implementation Completion Report on National Special Programme for Food Security (NSPFS), Benue State, Nigeria, 2020, 1-23.

Bureau of African Affairs. African Affairs Fact Sheet; US Department of State, 2010, Retrieved from https://2009- 2017.state.gov/p/af/rls/fs/2010/index.htm Degefa, T. Rural Livelihoods, Poverty and Food Insecurity in Ethiopia: A Case Study at Erenssa and Garbi Communities in Oromiya Zone, Amhara National Regional State. PhD thesis., 2015, Trondheim. Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU).

Dereje, T.R. Rural Livelihood Strategies, and Household Food Insecurity: The case of Farmers around Derba Cement Factory, Suluta Woreda, Oromia Regional State: A Thesis Submitted to the School of Postgraduate Studies of Addis Ababa University in Partial Fulfilment of Requirements for the Degree of Masters of Arts in Sociology., 2016. ( Unpublished).

Dilrua, K.; Roy, B.C. Rural Livelihoods Diversification in West Bengal: Determinants and Constraints. Agricultural Economics Research Review, 2012, 25(1), 115-124.

Dilrua, K.; Roy, B.C. Rural Livelihoods Diversification in West Bengal: Determinants and Constraints. Agricultural Economics Research Review, 2012, 25(1),115-124.

Ellis, F.; Freeman, H.A. The Determinants of Rural Livelihoods Diversification in Developing Countries. Journal of Agricultural Economics, 2017, 51, 289-302.

Etuk, E.A.; Udoe, P.O.; Okon, I.I. Determinants of Livelihood Diversification among Farm Households in Akamkpa Local Government Area, Cross River State, Nigeria. Agrosearch, 2018, 18(2),101-112.

FAO. Food and Agriculture Organisation, High Food Prices and Food Security: Threats, Opportunities and Budgetary Implications for Sustainable Agriculture. Luanda: Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations, 2010.

FMARD. Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, Nigeria, 2006.

Gani, B.S.; Olayemi, J.K.; Inoni, O.E. Livelihood Diversification Strategies and Food Insecurity Status of Rural Farming Households in North Eastern Nigeria. Economics of Agriculture, 2019, 66(1), 281-295.

Haddabi, A.S.; Ndehfru, N.J.; Aliyu, A. Analysis of Food Security Status Among Rural Farming Households in Mubi North Local Government Area of Adamawa State, Nigeria. International Journal of Research-Granthaalayah, 2019, 7(7), 226-246.

Idowu, B.O. Social Capital Dimension and Food Security of Farming Households in Ogun State, Nigeria. Journal of America Science, 2014, 7(8), 776-783.

Ihimodu, I.I. Marketing of Agricultural Products and the Food Security Programme in Nigeria. Paper Presented at The 13th Annual Congress of the Nigeria Rural Sociological Association at LAUTECH, Ogbomosho, Nigeria. 2014, 25-28.

Kassie, G.W. Livelihood Diversification and Sustainable Land Management: the case of North East Ethiopia. A thesis presented to the higher degree committee of Risumeikan Debre Markos University, Asia Pacific University in Partial Fulfilment of the Degree of Master of Science in International Cooperation Policy, 2016.

Kilic, C.I. The Role of Income Diversification During the Global Financial Crisis: Evidence from Nine Villages in Cambodia. Working Paper, 2019.

Kuwornu, J.K.M.; Suleyman, D.M.; Amegashie, D.P.K. Analysis of Food security status of farming households in the Forest Belt of the Central Region of Ghana. Russian Journal of Agricultural and Socio-economic Sciences, 2013, 1(13), 26-42

Kuwornu, J.K.M.; Suleyman, D.M.; Amegashie, D.P.K. Analysis of Food Security Status of Farming Households in the Forest Belt of the Central Region of Ghana. Russian Journal of Agricultural and Socio-economic Sciences, 2013, 1(13), 26-42.

Kyeremeh, K.M. Assessing the Livelihood Opportunities of Rural Poor Households: A Case Study of Asutifi District; M.Sc. Thesis submitted to the Department of Planning, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology Kumasi, Ghana, 2014.

Martin, S.M.; Lorenzen, K.A.I. Livelihood Diversification in Rural Laos. World Development, 2016, 83, 231–243.

Mattthew-Njoku, E.C.; Nwaogwugwu, O.N. Cultural Factors Affecting Livelihood Strategies of Rural Households in South East Nigeria: Implication for Agricultural Transformation Agenda. Russian Journal of Agricultural and Socio-Economic Sciences, 2014, 12(36),18-26.

Mohammed, A.; Fentahun, T. Intensity of Income Diversification among Small-hold Farmers in Asayita Woreda, Afar Region Ethiopia. Cogent Economics and Finance, 2020, 8,1-17.

National Bureau of Statistics (NBS). Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development Collaborative Survey on Nigerian Agriculture Sample Survey, 2012, Draft Report, 1-194.

Nghiem, L.T. Activity and Income Diversification: Trends, Determinants and Effects on Poverty Reduction. the case of the Mekong River Delta. A Thesis Submitted to the University of Erasmus Rottedndam, for the Award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in Economics, 2010.

Okpokiri, C.I.; Agwu, N.M.; Onwukwe, F.O. Assessment of Food Security Status of Farming Households in Abia State, Nigeria. The Nigerian Agricultural Journal, 2017, 48(2), 93-98.

Omonfonwan, E.I. Livelihood Diversification and Food Security Status of Small Scale Oil Palm Farming Households in Niger Delta Region, Nigeria. Pre-Data Seminar Presented at Department of Agriculture Economics and Farm Management, Federal University of Agriculture, Abeokuta-Ogun State Unpublished, 2018.

Oni, O.A. Fashogbon, T.A. Social Capital Dimension and Food Security of Farming Households in Ogun State, Nigeria.” Journal of American Science, 2012, 7(8), 776- 783.

Onunka, C.N.; Olumba, C.C. An Analysis of The Effect of Livelihood Diversification on The Food Security Status Of The Rural Farming Households in Udi, Local Government Area of Enugu State. International Journal of Agricultural Science and Research, 2017, 7(6),389-398.

Saha, B.; Bahal, R. Livelihood Diversification Pursued by Farmers in West Bengal. Indian Research Journal of Extension Education, 2014, 10(2), 1- 9

Saha, B.; Ram, B. Livelihood Diversification Pursued by Farmers in West Bengal. Indian Research Journal of Extension Education, 2010, 10(2):1-9

Sowami, Y.O. Effects of Rural Infrastructure on Livelihoods Diversification And Food Security Status of Households in Ogun state, Nigeria. Thesis submitted to the Department of Agricultural Economics and Farm Management, Federal University of Agriculture, Abeokuta for the Award of Masters of Science in Agricultural Economics, 2018.

Tashikalma, A.K.; Michael, A., and Giroh, D.Y. Effect of Livelihood Diversification on Food Security Status of Rural Farming Households in Yola South Local Government Area, Adamawa State, Nigeria. Adamawa State University Journal of Agricultural Science, 2015, 3(1), 33-39.

Umeh, J.C.; Ogah, J.C.; Ogbanje, C. Socio-economic Characteristics and Poverty among small scale farmers in Apa Local Government Area of Benue State, Nigeria. International Conference on Food and Agricultural Sciences, 2013, 55(20), 106 – 111.

Yared, A. Household Resources, Strategies and Food Security: A Study of Amhara Households in Wagada, Northern Shewa. Addis Ababa, AAU Printing Press, 2012. Yusuf, S.A. Effect of Urban Household Farming on Food Security Status in Ibadan Metropolis, Oyo State, Nigeria. Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 2013, 60 (1), 61-75.